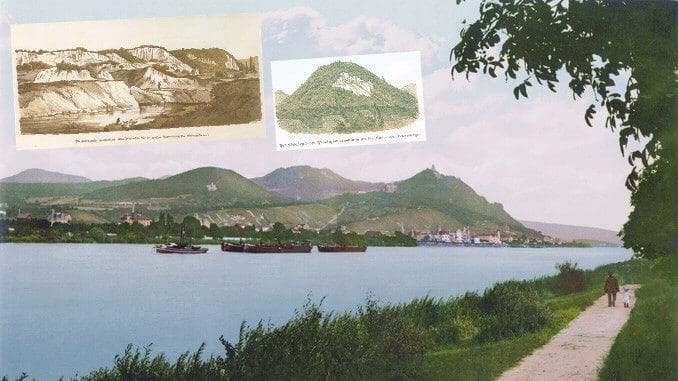

For centuries, trachyte, latite and basalt have been mined for in the Siebengebirge. The quarries almost destroyed our region. Hardly anything has remained of Mount Stenzelberg, which today is an abandoned quarry. The same goes for Mount Weilberg, an abandoned quarry and natural monument.

Trachyte from Mount Drachenfels

Already the Romans mined for trachyte at Mount Drachenfels. In Bonn and Cologne, and even in Xanten and Nijmegen, they built fortifications with Drachenfels trachyte. From the middle of the 13th century onwards, the Cologne Cathedral came into being, large parts with Drachenfels trachyte. Yet, the cathedral remained unfinished.

In 1823, repair work began on the Cologne Cathedral, and the masonry wanted Drachenfels trachyte. At Königswinter, the local stonemasons were eager to get in business with them right away. However, many locals, Prussian officials and even the Crown Prince, wanted to protect Mount Drachenfels and the medieval castle ruin. Years of embittered confrontations in the media and in court followed. In 1829, the Prussian Ministry of the Interior ordered the suspension of all quarrying. Nonetheless, the confrontations continued until 1836, when the Prussian state bought the mountain top.

Latite from Stenzelberg and Wolkenburg

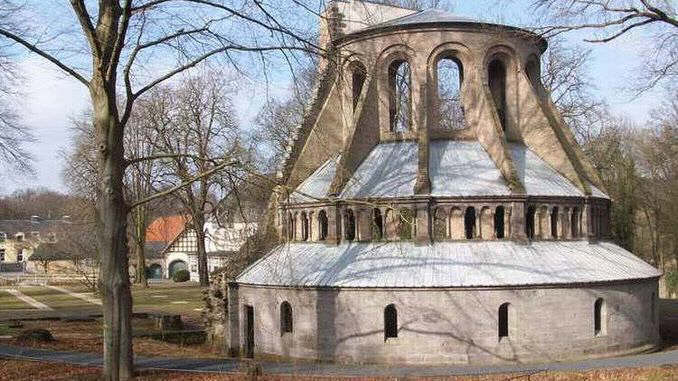

When the monks of Heisterbach Abbey started building their abbey church in the High Middle Ages, they mined for latite from the nearby Stenzelberg.

In early modern times, Mount Wolkenburg was also used as a quarry. By then, the medieval castle had already fallen apart. The fine latite was perfect for the fronts of representative Baroque and Rococo buildings, so ambitious stonemasons asked for it.

Today, we find Wolkenburg latite at numerous fine addresses all around Bonn, back then capital of the electorate of Cologne. For instance Bonn’s town hall, Poppelsdorf Castle, and in the Prince-Elector’s castles Augustusburg and Falkenlust at Brühl. In Königswinter, Wolkenburg latite was used for the Siebengebirgsmuseum Königswinter, Haus Rebstock in Hauptstraße, the St. Remigius church and at the wine fountain in front of the town hall, Drachenfelsstraße. Many of the way crosses along the Petersberg Bittweg are made of latite. Some older crosses have a base made of trachyte.

Basalt mining – huge quarries in the Siebengebirge

Things got even worse in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when basalt was needed for the construction of roads and railways. Large quarries were opened at the mountains Weilberg, Petersberg and Ölberg.

Finally, the damage to nature alarmed many people, they founded associations for the protection of the Siebengebirge. Later, they merged to form the Verein zur Verschönerung des Siebengebirges (VVS).

Justizrat Humbroich

On the way to the top of Mount Ölberg, you will pass a viewpoint called Humbroich-Platz. From here, you have a wonderful view across the Rhine valley. This place honors Justizrat (an honorary title bestowed by the Prussian legal authorities) Humbroich from Bonn, a devoted nature conservationist. He and his association “Verein zur Rettung des Siebengebirges” saved many beautiful places in the Siebengebirge. He has rendered an outstanding service to Mount Petersberg.

Oberpräsident von Nasse

The Prussian Minister of Agriculture, von Hammerstein, also sided with the nature conservationists, and above all Berthold von Nasse, the Oberpräsident of the Rhine Province. Back then, the Oberpräsident was the supreme representative of the Prussian crown in a Prussian province. He only approved new railway lines in our region if they did not endanger the Siebengebirge. Moreover, he did not approve any new railway line that would transport stones. After all, no quarry would pay off without a favorable connection to the railway network to transport the stones. The Oberpräsident even organized the boycott against basalt from the Siebengebirge, and many city along the Rhine joined in. They had roads and pathways built, so they were influential clients.

The Nasseplatz, an open quarry just below Margarethenhöhe, honors him still today.

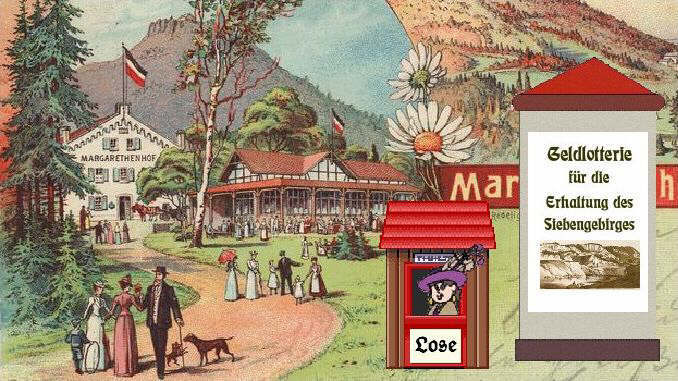

A lottery for the Siebengebirge

Back then there were no nature conservation laws with possible sanctions. The only option was to buy out as much land and existing quarries in the Siebengebirge as possible and then close them. This required a lot of money, and in the worst case a right to dispossess quarry owners. In 1897, the VVS submitted a request to the Prussian authorities, asking for a lottery to get money and the right to dispossess.

Now there was a conflict of interests. The protection of nature stood not only against the interests of the quarry owners, but also against those of the quarrymen. We also have to think of those indirectly affected, like the Heisterbach Talbahn railway who mainly did freight traffic from the quarries to the factories. Finally tourism became important, too. Many people had discovered the Siebengebirge for trips, and their money supported the hotels, restaurants and public transportation.

Finally, in March 1899, Oberpräsident von Nasse could inform the VVS about the favorable decision. His Majesty Kaiser Wilhelm II had approved a money lottery with a net profit of 1,500,000 Marks for the preservation of the Siebengebirge, and also granted the right to dispossess. One year later, the VVS had collected enough money to buy out wide areas in the Siebengebirge and to close down numerous quarries.

After long negotiations, purchase of land and legal disputes, the VVS could close the last quarry on Petersberg in April 1908. But at other mountains in the Siebengebirge the quarries continued, for example at Weilberg and Stenzelberg, of which not much has remained.

Be the first to comment