Rhineland, 1918/1919. The armistice had put a temporary end to the fighting in the Great War, the allied occupation of the Rhineland began. Martial law remained in force, and the British fleet maintained its naval blockade.

After the revolt of the sailors in Kiel, the revolution spread throughout the country. Uncertainty about the future shaped the mood in the Rhineland.

Retreat

According to the armistice, German troops had to evacuate the left bank of the Rhine before 6 a.m. on 4 December. The soldiers, who were still in France and Belgium, were hurrying back. Many people were waiting for them at the roads and bridges, hoping that the soldiers would be able to give them news of their loved ones.

The villages of Königswinter and Dollendorf looked like army camps. Countless units of troops marched through the streets, either on foot, on horseback or in trucks and carts. The ferry ran day and night to transport people and material from the left bank to the right bank of the Rhine, as did the ships of the Köln-Düsseldorfer line and other companies. Pioneer battalions built pontoon bridges across the Rhine. Officers and crews needed accommodation. Despite the defeat, the locals did their best to welcome the troops in a friendly manner.

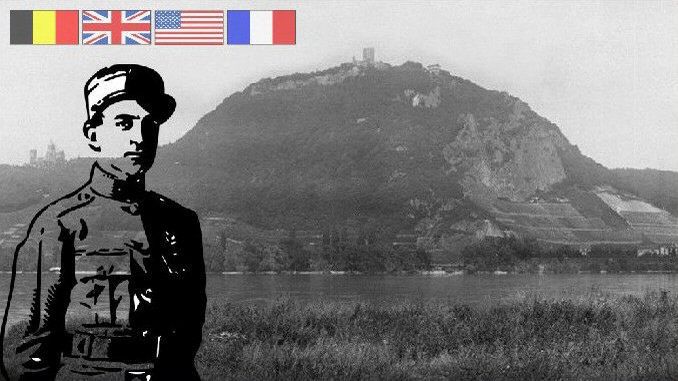

Allied troops on the Rhine

As the war propaganda had promised victory until the last moment, the defeat took people completely by surprise. Then, the situation suddenly changed. Several dozen American, Belgian, British and French divisions occupied the left bank of the Rhine and “bridgeheads” on the right bank. A 50-km-wide strip on the right bank of the Rhine was now a demilitarized zone. The war was over, but neither the Rhinelanders nor the occupying soldiers who had come from afar were yet at peace.

By December 15, the whole Cologne area was under British occupation. Here, British time applied, so in Cologne it was an hour earlier than in the rest of Germany. The British authorities restricted freedom of press and assembly, imposed nightly curfews and forbade carnival. Many families had to provide accommodation for English soldiers. Soon Mayor Konrad Adenauer established good working relationships with the British military authorities, and both sides got along quite well.

The idea of an autonomous Rhineland

Uncertainty about the future shaped the mood in the Rhineland, especially as in France, some were thinking of separating the Rhineland from Prussia, the German Reich or even annexing it.

Geographically and culturally, the Rhineland was closer to Western Europe than to Prussia. Politically, the conflicts of the past cast a lingering shadow over the two neighboring peoples on the Rhine. The lost provinces, the proclamation of the German Empire at Versailles, and then the devastating war. For France, Germany was too powerful an enemy economically and demographically. There had been no fighting on German soil, whereas vast areas in France and Belgium were devastated, mined and poisoned, creating a hostile environment for years to come.

“Buffer State”

Thus, the idea of a “buffer state” was born. People on both sides of the Rhine discussed it, and in both Germany and France there were opponents and supporters of an autonomous and demilitarized Rhineland.

Already on November 10, 1918, one day before the armistice and one day after the proclamation of the Republic in Berlin, there was talk in Cologne of a Rhine Republic within the framework of the Reich, but nothing happened afterwards. Yet, an agreement had to be reached with France that would allow the two countries to live together in peace.

Adenauer

Also Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967), since 1917 mayor of Cologne, entertained these thoughts. At that time, Konrad Adenauer, later the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, was the mayor of Cologne. On February 1, 1919, he delivered a speech to representatives of occupied territories. If Prussia was divided and her Western provinces were joined into a “West German Republic”, he said, the might of the old “belligerent cast” that had dominated Prussia could be broken. Since then, Adenauer has been a highly controversial man. Yet, he supported Rhineland autonomy within the German Empire.

Dorten

Other separatists demanded independence for the Rhineland. On June 1, 1919, a group around Dr. Hans Adam Dorten (1880-1963) occupied the government building in Wiesbaden, Hesse, supported by French occupation troops. Dorten proclaimed the Rhine Republic within the German Empire. French intellectuals and journalists encouraged him and the French General Mangin. However, strikes and mass demonstrations forced him to retire four days later under French protectorate.

Free State of Prussia (1919-1932)

Many people thought that Prussia, as a military and authoritarian state, would weigh too heavily on the young republic. There were serious plans to divide it. Yet, Prussia stayed and obtained a democratic constitution.

Finally, the restrictive three-tier voting system was abolished in favor of universal suffrage and all men – and women! Unlike other German states, there was still a democratic majority in Prussia. Throughout the years of the Weimar Republic, the Free State of Prussia was a “pillar of democracy”, as Gustav Stresemann put it.

Treaty of Versailles

On June 28, 1919, the Treaty of Versailles was signed. The Rhineland remained demilitarized, and Allied troops occupied the left bank of the Rhine and the bridgeheads of Cologne (British sector), Koblenz (American sector) and Mainz (French sector) for a period of 5 to 15 years. In addition, the Allies reserved the right to occupy Germany in case of breach of the treaty.

In addition, the Allies set up the Allied High Commission for the Rhine Territories (HCITR). It was thus a civilian commission representing governments instead of a military commission representing armies. The chairman was the Frenchman Paul Tirard.

The situation is getting worse

When French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr area in 1923, tensions between French troops and the locals in the occupied Rhineland increased. French troops also entered Bonn and Königswinter, some 350 people were expelled. Many young men joined separatist groups.

By September 1923, Reich Chancellor Stresemann had ended the passive resistance. Considering the devastating consequences, he had no choice. However, for the inhabitants of the occupied territories, the situation was getting even worse. For months, they had fought, endured the privatizations and resisted the exhausting pressure. And now it seemed that it has all been in vain. Not a single foreign soldier had left. Already the right, and not only the right, was talking about the “surrender to the Ruhr”.

Demoralized Rhinelanders

The economy was at a standstill. Almost no one had a job, and with devastating inflation, wages were soon worthless on payday night. Help for the unemployed was barely enough to live on – if merchants and farmers even accepted almost worthless paper money. Many people no longer knew how to support their families.

The Reich government was preparing a monetary reform, but the new, sound currency would not be introduced in the occupied territories. There was even talk of cutting support payments to the occupied territories to reduce the amount of money in circulation.

In this disastrous situation, the members of the Reich government seriously considered separating the occupied territories in the Rhineland from the Reich and leaving them to their own devices. The people felt abandoned.

The Separatist “Rhenish Republic”

Meanwhile, the separatist parties had regrouped, Dorten and Smeets had formed the “Vereinigten Rheinischen Bewegung” with Josef Friedrich Matthes as chairman. As the situation was getting worse and worse, they thought it was time to act

On 21 October they occupied Aachen in the Belgian zone, three days later Bonn in the French zone and finally Koblenz on 25 October. They seized public buildings and proclaimed the “Rhine Republic” and raised the red-white-green Rhine flag. At Koblenz Castle they formed a “provisional government of the Rhine Republic” with Matthes at its head. The French commander confirmed this a day later. However, it was obvious that the majority of the people were not on the side of the separatists.

The “provisional government” raised its own troops, the “Rhineland Protection Forces”. Among them were people who had been expelled or had lost everything, but also criminal elements. The situation worsened when the “provisional government” ordered “requisitions”. Then the troops invaded the villages and “requisitioned” material goods and food to an extent that far exceeded their needs.

This looting shaped the image that the people of our region had of the separatists. On October 25, 1923, the separatists “raided” Königswinter, as a local newspaper wrote. This choice of words is understandable if we realize what happened: a group of non-residents, for the most part, entered the town, occupied the town hall with guns and harassed the citizens, all under the protection of French soldiers.

A battle in the Siebengebirge

The separatists often drove to nearby villages to requisition food, or, from the locals’ point of view, to steal it. People formed self-defense groups. On November 15, 1923, a fight broke out between a group of separatists and the defenders of the village near the village Aegidienberg, in which fourteen separatists and two locals died. A monument in Aegidienberg-Hövel reminds us of this battle.

An atrocious end

So Rhineland citizens beat the separatists out of their villages and cities, even killed them. That may be difficult to understand at first. However, the separatists failed because they didn’t have the citizens on their side. These didn’t feel liberated, but threatened, and they didn’t believe in the separatists’ patriotic conviction. Moreover, the officials of the “Rhenish Republic” were not in a position to supply their people without requisition and, worse still, to keep away criminal elements. Finally, the separatists were supported, at least tolerated, by the French military.

The hour of liquidation had come. The police, but also nationalist paramilitary units from Germany, had no difficulty in crushing the Rhine militia. Finally, France and Great Britain agreed to put an end to separatist movements, so the remaining separatists went into exile, and on December 28 the “Rhenish Republic” was officially done away with.

Occupation of the Rhineland | See more

YouTube, The Great War, The Allied Occupation of Germany

20th century

The short 20th century | The Great War | German Revolution 1918/19 | Occupation of the Rhineland | Weimar Republic | Nazi Germany | World War II | Federal Republic of Germany

Be the first to comment