In the Roman era, the Siebengebirge was a military area at the border of the Roman Empire, province Germania Inferior. Roman quarries at Drachenfels supplied stones for Bonn, Cologne, Xanten and Nijmegen. For about 500 years, the events within the Empire and its long defense fight determined life on both sides of the frontier.

Therefore, let us look at 500 years Roman era, at the border of the Roman Empire. Yet, we know only very little about the people who lived in and around the Siebengebirge back then. What we know comes from Roman sources, and the archaeologists have found only very little here from the Roman era. Certainly, right at the frontier, a “normal” life was not possible, neither for the Romans nor for the Germanics.

Border region

Caesar’s Gallic War had brought Roman legions to the Rhine. After his victory, the Rhine was the border between Roman territory on the left bank and the free Germania on the right. After Caesar’s victory, Germania disappeared for a while from the Roman historians’ field of vision. During the next years, the civil war within the Empire caught their attention.

Agrippa and the Ubii

Only in connection with the governorship of the Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa do we hear again about the Rhine border. Agrippa was a close companion of Octavian, Caesar’s heir, the later emperor Augustus. During his two governorships in Gaul in 39/38 BC. and in 20/18 BC. he had garrisons and army routes built. Around 16/15 BC, a Roman road went from the Roman city Augusta Treverorum (today’s Trier) to Neuss in Germania.

Back then, the Ubii lived on the right bank between the rivers Sieg and Main. They traded with the Romans, and Ubian men fought as auxiliary troops in the Roman army – even against other Germanics. Thus, they made enemies of their Germanic neighbors and were almost wiped out when Agrippa intervened. He campaigned on the right bank of the Rhine and resettled the Ubii on the left bank. From Aachen down to the Ahr Valley, Ubian settlements came into being, among them Bonn and of course the “oppidum ubiorum”, later Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, today’s Cologne.

Rome’s attack: Drusus and Tiberius

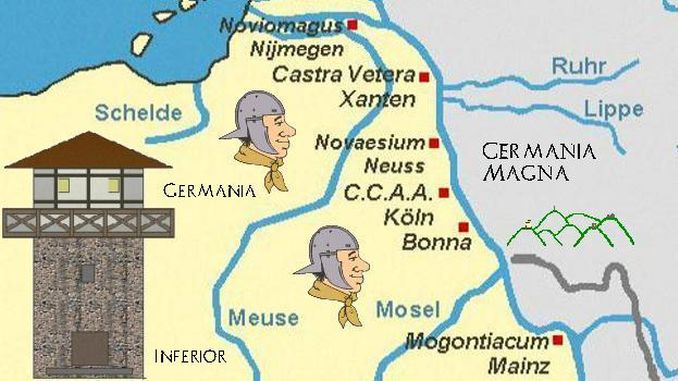

After a disastrous defeat against the Germanic Sugambri in 15 BC, Emperor Augustus prepared a large-scale attack. Thus, he commanded five, perhaps even six legions to the Rhine and stationed them in strategically important places. Nijmegen (Noviomagus), Neuss (Novaesium), Xanten (Vetera) where the Lippe river flows into the Rhine, Mainz (Mogontiacum) where the Main river flows into the Rhine, in Moers/Arsberg (Asciburgium) where the Ruhr river flows into the Rhine, and also in Bonn (Bonna). Actually, Drusus’ soldiers founded Bonn around 11 BC. At the same time, the Romans conquered much of today’s Southern Germany, and the Danube became the new border.

General Drusus conquered large regions between the rivers Rhine and Elbe. On the way back he fell off his horse and died from the injuries suffered. Now his brother Tiberius, the later emperor, became commander in chief at the Rhine border (8-7 BC). With a double strategy of military superiority and skillful diplomacy, he managed to pacify the Germanic tribes between the rivers Rhine and Weser. The Sugambri, still embittered enemies of Rome, had to resettle on the left bank of the Rhine.

Rome assumed that it had achieved its aims. At the rivers Rhine, Lippe, Ems, Lahn and at the North Sea new bases for Roman military and administration came into being. Today we know about a civilian settlement already back then, Waldgirmes in Hesse. But already in the year 1 AD riots occurred, the Roman historian Velleius Paterculus speaks of the “Immensum bellum” in Germania. Only in the years 4-6, Tiberius and his army could crush the uprisings. But then a rebellion in Pannonia and Dalmatia broke out and Tiberius set out to crush it. Publius Quinctilius Varus took over the supreme commander in Germania.

Varus Battle

Varus set out to impose Roman law in right bank Germania, and to turn it into a Roman province. But on September 9, the catastrophe occurred. Varus and three Roman legions were ambushed and massacred on their way back from the summer camp in the interior of Germania to their winter quarters at the Rhine. The leader of the rebellious Germanics was Arminius, a Cherusci chief. When he was a boy, the Romans had taken him hostage, so had he grown up in Rome. He had joined the army and become a capable officer. By the time of the battle, he was the commander of Germanic auxiliaries.

In Rome, Emperor Augustus was shocked. The Roman historian Suetonius reported that he banged his head against the door, again and again, calling out, “Varus, Varus, give me my legions back!” He never assigned the names of those legions again, but he did not change his policy towards Germania either. Shortly after, eight of altogether 25 Roman legions stood at the Rhine. Again Tiberius took over the supreme command, and again he secured the border.

Tiberius

When Augustus died, Tiberius ascended to the throne. He assigned the supreme command on the Rhine to his nephew Germanicus. Like his father Drusus, Germanicus wanted to bring Germania under Roman rule, and he wanted revenge. In 15, he came to the site of the Varus battle and buried the dead. On the way back, a part of his army was trapped and almost annihilated. In the following years, several bloody fights took place. The Romans the upper hand, yet they had suffered heavy losses. Eventually, Germanicus withdrew and stopped the campaign.

In Rome, Emperor Tiberius saw that the campaigns demanded more and more Roman soldiers’ lives, without achieving a crucial victory. In winter 16/17, he recalled Germanicus. From now on, he sought to secure the province of Gaul by strong military presence at the Rhine border. From now onwards, the Roman military protected the frontier, all along the Rhine from Bonn in the south to the Northern Sea. On the left bank, forts, harbors, garrisons, streets, and also civilian settlements came into being. Farmers tilled the soil, and soon the Roman manors (villae rusticae) could supply the legionaries.

Roman quarries at Mount Drachenfels

The Siebengebirge were in sight of the Roman legion camps in Bonn, even Cologne. Although our region was part of the free Germania Magna, it remained important to the Romans, most of all for economic reasons. From around 50 onwards, they ran large trachyte quarries at Mount Drachenfels and transported them northwards. In Bonn and Cologne, even in Xanten and Nijmegen Drachenfels trachyte was used. Still today, these quarries remind us of the Roman era in the Siebengebirge.

Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium

Germanicus had nine children with his wife Vipsania Agrippina, a daughter of Agrippa. One of them, Agrippina the Younger, was born in today’s Cologne, during the years of his campaigns against the Germanics. She later became the wife of Emperor Claudius, and was mother of the later emperor Nero. It is to her that Cologne owes its outstanding position as Roman colony, Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. Agrippina was very conscious of her power and did not shy away from plots and murder. Eventually, she was murdered at the orders of her own son Nero.

Batavian Revolt

In the last year of Emperor Nero’s reign, the Roman Empire got into a state crisis (68/69) that involved the Rhine legions. A bloody civil war followed between Vitellius, supported by the Rhine legions, and Vespasian, supported by the eastern and also the Danube legions. When Vitellius ordered more auxiliary troops to be recruited from the Batavians in today’s Holland, they revolted against Rome, led by Iulius Civilis, a former Roman officer. Various other Germanic tribes joined them. They destroyed the garrisons in Xanten and in Bonn and conquered Cologne.

Eventually, Vespasian defeated Vitellius and ascended to the throne (69-79). Now he had legions at his orders to crush the Batavian revolt and re-establish Roman control over Germania Inferior. In 74, Vespasian established control over Agri Decumates, the land between the rivers Rhine and Danube, much of today’s Baden-Württemberg. Thus, the border became a lot shorter and easier to defend.

Roman Bonn

Now the legionaries needed stones from the Roman quarries at Drachenfels to build a new garrison. Further south a civilian settlement grew and prospered, the “Vicus bonnensis”. When the archaeologists searched the area in 2006, they were very impressed by the finds. Obviously, the Vicus was a Roman city with all comfort! Bonna even had a port. We can see many of the finds at Haus der Geschichte in Bonn.

The Limes

Vespasian’s younger son Domitian (81-96) pushed across the Rhine again and defeated the Germanic Chatti in two wars (83-85). After this demonstration of Rome’s military power, he converted the military zones Germania Inferior and Germania Superior into Roman provinces. Germania Inferior (Lower Germania) covered parts of today’s Netherlands, Northwest Germany and Belgium, its capital was Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, the later Cologne. Germania Superior (Upper Germania) covered parts of today’s Switzerland, France and southwest Germany, its capital was Mogontiacum, the later Mainz.

To protect the wealthy provinces of Germania Superior and Raetia, Domitian had a border fortification built. The Limes reached from Rheinbrohl in today’s Rhineland-Palatinate to Eining in today’s Bavaria. Yet, the Limes was no impermeable border by which the Roman Empire walled itself off; there were quite peaceful contacts and trade with Germania in the following hundred years.

Roman Citizens

Under the Severan dynasty (193-235), the provinces Germania Inferior and Germania Superior enjoyed a time of relative peace. In 212, Emperor Caracalla (211-217) granted full Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Roman Empire. So, inhabitants of Bonn and Cologne were Roman citizens. Caracalla also raised the legionaries’ wages. Thus, more money came into the provinces, there was building again and people were quite well. Also on the left bank of the Rhine, in the “Barbaricum”, many Roman goods were found. Obviously, the Germanic upper class, which could afford Roman goods had developed an appetite for them. Yet, most people in the free Germania were poor, and the prosperity in the Roman provinces aroused envy.

More and more often the Franks and Alamanni raided the Roman provinces, and more and more often the Roman troops came too late.

those described are official macro-historical facts

it’s more interesting to know what happened in normal periods of peace

what were the daily interactions between Romans and Germans along the Rhine border

were Franks nearly allied with Rome?

Yes, that’s right, history books don’t write much about the daily life back then, let alone people like you and me. We learn much more from good historical movies and period dramas. Unfortunately, we know little about the time of the Romans and Franks on the Rhine, and we have only Roman sources. From the end of the 3rd century onwards, the Franks were allowed to settle on the left side of the Rhine, they became Roman federates and served in the Roman army. The Franks on the right side of the Rhine remained enemies. If you know German, I have a longer story about a fictional Roman-Ubian family on my German site, Leben an der Rheingrenze (Life on the Rhine border), that is about everyday life back then.

https://roemer.rheindrache.de/

I plan to publish it in English, yet that will take a couple of weeks.

Take care and stay safe! Petra