The Rhineland around 1530, the time of the Protestant Reformation. Although the Rhineland remained Catholic, there were Lutheran, Anabaptist and Calvinist congregations.

At first, the Protestant Reformation had little resonance in our region. However, the Archbishop of Cologne, Hermann von Wied, revealed the need to reform the Catholic Church, but nothing happened. Finally, he brought theologians of the Reformation to the country.

Habsburg, a world power

Emperor Charles V was one of the most powerful men of his time. He ruled an empire in which “the sun never set”: vast territories in Europe, inherited from his Spanish and Burgundian ancestors, and Spanish colonies in the Americas and the Philippines. Charles V was the only Habsburg emperor who, at least for a few years, united the entire power of the Habsburgs in his hands.

Reformation and politics

Martin Luther’s reformation was spreading in Germany. Some princes converted, for instance the rulers of Hesse, Palatinate, Saxony, and Württemberg. They did so for conviction, but also for political calculations: by becoming a Lutheran, they did away with the Pope’s authority and the overwhelming dues to the curia in Rome. Instead, they could build up their own Lutheran national churches and strengthen their position against the Catholic Emperor. Obviously, the Protestant Reformation was no longer a matter of theologians only.

Emperor Charles’ struggle

Charles V must have hated to see reformation spread, but he could hardly interfere as the continuous war against France kept him abroad. It came even worse for him: after defeating the Hungarians in the battle of Mohacs in 1529, the Ottoman Turks threatened the Empire. In 1529, the siege of Vienna began. Thus, Charles made a compromise: the Lutherans could practice their religion until a general council on issues of faith would restore unity.

Back then in the Siebengebirge

Since the late Middle Ages, large parts of our region, including the villages Oberdollendorf, Niederdollendorf, Küdinghoven, Oberkassel and Honnef were part of the Duchy of Berg.

William, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

By the time of the reformation, the duchies of Jülich, Cleves (on the left bank of the Rhine river) and Berg (on the right bank) were united under one family. The ruling Duke William (1539-1592) was a mighty man. His sister Anne of Cleves was the fourth wife of Henry VIII of England.

He was an open-minded humanist and a tolerant ruler, in his lands lived Catholics and Protestants.

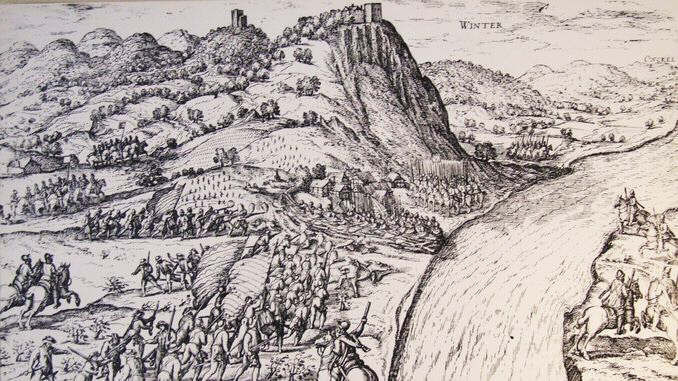

Gelderland – the Emperor makes an example

In 1543, Duke Wilhelm of Jülich-Cleves-Berg claimed on Gelderland, which would have made him a regional super-power. That brought Emperor Charles V into the arena. After his long absence from Germany, he could now impose his will on a German Prince. When the Imperial troops marched through the town of Bad Honnef, they got into fights with the Duke’s men, and many houses were destroyed. Finally, Duke William had to surrender and give up Gelderland in the treaty of Venlo of 1543. Moreover, he had to proceed against reformation.

War against the Lutherans

At last, Charles V made peace with France and the Ottoman Sultan. Meanwhile, reformation had spread further, only Austria, Bavaria and the three ecclesiastical states (under the control of a bishop) Cologne, Mainz, and Trier had “officially” remained catholic, yet also here the Reformation found followers.

Finally, the Council of Trent (1546-1563) came together on the Emperor’s urging. Yet, it was the Pope’s council, not a German one; therefore the Lutherans stayed away. Again Charles V took up arm. His troops, enforced by Spanish and Italian mercenaries, prevailed, and Charles V was at the height of his power.

A year later, at an Imperial Diet in Augsburg he “dictated” a religion to the Lutherans, the Augsburg Interim (1548). But the Lutherans mostly resented the interim, and also the Catholic princes feared the increasing dominance of the Emperor and Spain. When Charles suggested his son Philip II of Spain as his successor, the princes, supported by the French King, rebelled against him. After a devastating defeat, Charles V had to retreat (1556). His son Philip II of Spain inherited the Spanish empire, his younger brother Ferdinand the Austrian lands.

Augsburg peace

The new Emperor Ferdinand I (1556-1564) made peace with the Lutherans. The Augsburg Peace of 1555 stated that the princes could choose the religion in their lands (in Latin “cuius regio, eius religio), in other words: the prince could freely decide to be either a Catholic or a Lutheran, and his decision was binding for his subjects, they had no freedom of religion. The Augsburg Peace also stipulated that bishops could convert, in that case, however, they had to give up their ecclesiastical territories.

Calvinists in the Rhineland

After the defeat of Charles V. and the Augsburg Peace, the Protestant Reformation in our region grew stronger again. However, now John Calvin’s teachings spread, not Luther’s. John Calvin had founded the “Reformed Church” in 1541 in Geneva.

In many villages Calvinist parishes came into being, also in Niederdollendorf and above all Oberkassel. But it was dangerous to confess to Calvinism, and these people could only meet secretly. The Augsburg Peace recognized the Lutheran, but not the Calvinist confession. Moreover, since 1566 the Calvinist Netherlands fought for their independence from Spain, so there was no way that the Habsburg authorities in Germany would tolerate Calvinist parishes within the Empire, right at the border to the Netherlands.

Anabaptists in the Rhineland

Even more than Calvinism, Anabaptism as preached by Menno Simons had gained ground in the villages on the right bank of the Rhine.

The Anabaptist movement had begun in Zurich. It was very complex, there were people who would consciously suffer injustice, but also militant and violent others to whom the aim justified the mains. The Anabaptists stood for believer’s baptism, that is to say adult believers opposed to infant baptism. Moreover, they demanded freedom of worship and rejected all church authority. This led to heavy prosecutions by the Catholic and Lutheran authorities.

The Mennonites were non-violent, even pacifistic, but nonetheless they were prosecuted. Since the Diet of Speyer of 1529, Anabaptists who did not recant could be executed on the spot, without legal proceedings. In the Rhineland, one tried to convert them and deported them if they refused, but also here arrests and executions occurred.

War of Cologne (1583-1588)

Prince-Archbishop of Cologne Gebhard I Truchsess von Waldburg had converted to Calvinism and married the woman he loved, Agnes von Mansfeld. According to the Augsburg Peace, that was his right, but he had to give up his territories. Yet, he refused to, and that was not only against the law, but also a highly political issue. As Prince-Archbishop of Cologne, he was an Imperial Elector, and his now Calvinist vote could have led to a Protestant majority in the Electoral College. The Cologne cathedral chapter replaced him by Ernst of Bavaria of the Wittelsbach dynasty.

Both sides took up arms. Gebhard got support from the Palatinate, the cathedral chapter from Bavaria and Spain. The Lord of the Drachenfels sided with him as well. During the next years there was violent fighting. Gebhard entrenched on Godesburg Castle close to Bonn, it was besieged and in 1583 conquered and blown up. The same year Königswinter was occupied and pillaged until it was finally rescued by Bavarian troops. Gebhard had to flee. Supported by Dutch troops, he took up the fight once again and conquered Bonn in 1587. But when the Dutch withdraw their troops in 1588, he had to give up.

In the course of the War of Cologne, many medieval castles and villages had been destroyed. Moreover, the Augsburg Peace, the peaceful side by side of confessions, had been violated, and both sides had called foreign troops into the country.

The Thirty Years’ War

Nevertheless, our region and the whole of Central Europe were not at the end of their troubles. Some 50 years later, the Thirty Years’ War between the European powers broke out, leaving behind a country reduced to ashes and depopulated.

Years of terror

Armies of mercenaries marched through the country. Paid late or not at all, they robbed, looted and killed. In 1638, Wolfgang Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg (1614-1653), wrote that in the Duchy of Berg only one sixth of the inhabitants had survived. Not only war, but famine and epidemics killed countless people.

Back then in the Siebengebirge

In 1632, the Swedish general Baudissin marched against the archdiocese of Cologne. In 1633, first the Swedes and then the Spaniards occupied Drachenfels Castle. Bands of soldiers – most of them mercenaries – caused damage to the villages. The castle Löwenburg was also destroyed.

In 1642, the Archbishop of Cologne had what was left of Drachenfels Castle destroyed. The time of castles had passed, they could no longer withstand the modern armaments and thus their maintenance had become too expensive.

The Peace of Westphalia

Finally in 1648, the peace of Westphalia was made in Münster and Osnabrück. Not only the emperor, but all the princes took part in the negotiations. The princes obtained more autonomy in their territories. After the war, the empire consisted of about 300 counties and duchies, and the political map had become a mosaic.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William,_Duke_of_J%C3%BClich-Cleves-Berg

Early Modern Period

Intro Early Modern Period | Lutherans, Calvinists, Anapabtists | Absolutism and wars of succession

Be the first to comment